By Lawrence Pettener

Who said Malaysian poetry in English was dead? Many have tried to convince me but they should read this lively new anthology. Here are 37 Malaysian millennial poets, all of whose work shows vital signs of vibrancy, picked from the 135 who answered the call for submissions.

A good number of these poets have been through the Creative Writing BA at Nottingham University Malaysia, and it shows; these poems are far from one-dimensional, with much in the way of experimentation, solid expression and bold confidence. One poet has tackled the difficult sestina form, while another’s work includes a villanelle. The BA was headed by the recently retired editor of this book, Malachi Edwin Vethamani.

The best here have managed to find ways to say something really worthwhile, including on social issues such as multicultural life, inter-generational issues and corruption. In their various forms, family relations are a recurring preoccupation as well.

Loshni Nair’s self-avowedly confessional work is as striking as anything in this collection, including treatment of abuse and mental health issues. Nonetheless,

Daddy

, a response to Sylvia Plath’s eponymous poem, works better as political comment than confessionally, opening with:

daddy, you twisted little

thief. thief four point six,

one point two, thief the billions,

then thief some more.

Kwan Ann Tan is more understatedly profound. In

Monsoon

we get the delightful

A man stands by the side of the river

with a fever so hot

that it might run away with him.

Further on in the same poem,

One family takes in a whole clan

of tortoises, beady eyes reflecting centuries

of cyclical movement.

The Secret History of the Peninsula

brings historical redress:

Marco Polo fetishises the Orient…

Chinese records

do not seem to remember him.

Zulfikri Ahmad’s

The Land of Forgotten Ancestors

is honest with regard to religious cultural observance. The image which ends

Santa’s Funeral

is stunningly surreal:

Grandma lies on the

bed untouched, while her favourite cup

flies in the air, hits the light bulb, and

turns the wooden house into a dark

place filled with greedy sobbing daughters.

In

Lost in Translation

Joseph Lu has to my mind, the most ingenious poetic image in the volume, one that reframes Malaysia’s multicultural condition:

Nothing’s lost. Or else: all is translation

And every bit of us is lost in it.

His poem

Banana

is as knowingly political as anything else here. Elsewhere he is enigmatic, as in his cool urban piece,

Last Stop

:

and I cremate, inside the vacant carriage, the tryst between

past and city

and when the rails ran out of sky, the midnight took me into

its burrow

It’s a rare gift, to pull off the abstract without it falling flat; Lu picks a fine line here between private meaning and engaging content and emerges at its terminus triumphant.

Yee Heng Yeh captures the aching ironies of a generational transition in his hauntingly successful sestina,

A Day in Childhood

:

They try not to think of mother –

after all, they are growing up; there’s no time for games.

This and his monologic

A Political Story

, which recalls playwrights Pinter and Beckett, together with Joseph Lu’s poems (above) are for me the standout works of the entire collection:

Whose money is better looking, is the life of the party,

speaks more confidently than whose?

Who is saying nothing? Who is deciding

what who means when who said what?

While the spoken word scene has awakened political consciousness for many, in this publication almost every poet’s work needs some attention to ensure the poems lift outwards from the page. Opportunities to make an impact at line ends, with their natural half-pause for breath, are wasted on articles, pronouns and prepositions; while some position them there to build tension or to ironic effect (a spoken word trope), most read as random placement. There’s a tendency in even the best poems here to place redundant commas at line ends, breathlessly. Breaks in tense agreement are arguably less distracting.

It will be interesting to see who’s still making waves in Malaysia’s poetry world in ten years from now, or even in five. Poet-Elder Wong Phui Nam predicts two or three will produce worthwhile work; editor Malachi Edwin Vethamani rates seven in his foreword. I would pick five to watch, in the following order: Yee Heng Yeh and Joseph Lu jointly, followed by Kwan Ann Tan, Zulkifri Ahmad and Loshni Nair.

Others featured here are no doubt better poets in development than their one or two non-representative poems might suggest. This is true of Hana Sudradjat, my mentee at the time of writing; Brandon Khaw also springs to mind, as does Yasmin Suraya Putera. If there are too many to mention, that’s because the bar for publication here is engagingly high. Other millennials such as Chloe Lim, Yanna Hashri and Ruo Min Toh are latent returners to the scene, having been diverted temporarily.

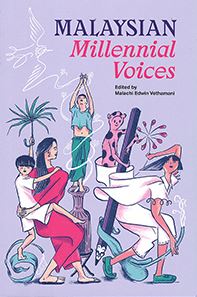

Poetry’s a hard sell at the best of times; publishers Maya Press have been courageous in taking the plunge, though I think this book is going to be a landmark publication for a long time to come (future editions might do even better with more tonally appropriate cover artwork than the present pastel collage).

Coupled with the 2017 Vethamani/Maya teaming of

Malchin Testament: Malaysian Poems

(winner, best English language book award at Anugerah Buku Malaysia 2020), this volume updates us, filling the gap in cataloguing the nation’s creative output in English. None can now justify the facile assertion that Malaysians are impervious to poetry.

To order a copy of Malaysian Millennial Voices, visit here .

About Lawrence Pettener

Originally from Liverpool, Lawrence Pettener works full-time in the Klang Valley as copy-editor, proofreader and writer, specialising in helping solo authors (including mentoring poets). He facilitates poetry-writing workshops, the most recent of which was for LevelUp. As Kwailo Lumpur, he writes comic material about Malaysian life, food especially. Find him at:

https://www.facebook.com/lawrencepettenerwriter/

and

http://www.lawrencepettener.com